26 August 2021

Article from July 2021 edition of INPractice

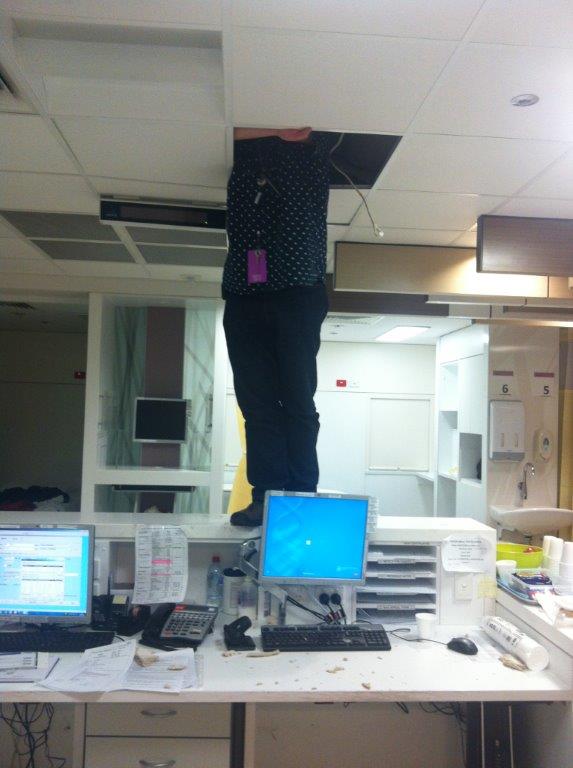

For mental health nurse Brenton Westell, poking his head through the ceiling of the Flinders Medical Centre was just another day on the job.

A patient with meth-induced psychosis had managed to barricade himself inside the ceiling of the emergency department.

"He was a patient in our short-stay unit, the extended care unit of the emergency department," Brenton explains.

"He believed that there were devices implanted in the ceiling that were monitoring him at his house and he decided he would need to escape through the ceiling to go home to look in his ceiling to check out these devices.

"He got up through an unlocked manhole in the bathroom and the whole area was contained by a firewall, so he couldn't get out. And we heard him in the ceiling space.

"So it was a bit of an unusual one and because of the risks involved we called the police and in that photo they were standing off to the right, in case they were needed.

"I said to my colleagues 'I'll see if I can talk him down'. I stood on the desk and opened up a little panel in the ceiling and he was sitting not far from me and we proceeded to have a conversation and I used some logic to convince him that it wasn't a good look for him to be in the ceiling of the ED of a hospital.

"We got a ladder and he worked his way down. The first thing he handed me when I stuck my head in was an 18-inch shifting spanner that had been left there by maintenance by mistake. So I was very pleased he was of the demeanour to hand it to me rather than chuck it at me," Brenton says.

"The police had indicated they might have to send a dog up there, but I told them it wasn't the sort of place that a dog could get up into, it was a suspended ceiling. I think I said something in passing, 'Look if you've got a possum that might be useful', but they didn't have the same sense of humour as me ...

After 42 years in the health profession, Brenton, a former ANMF (SA Branch) organiser, retired in March this year to look forward to a new life of footy and fishing and being a doting granddad to his new and first granddaughter Daisy ("the best baby in the world").

Brenton, the Australian-born son of "10-pound Poms" who settled in Salisbury North, is a volunteer worker for "grassroots" footy club the Unley Jets, a team he's been involved with "since my kids started playing in 2003 ".

His nursing career dates back to the '70s. "After completing high school in 1978 I was accepted into the 'pilot' undergraduate program, then in its fourth year, at the Sturt College of Advanced Education," Brenton says.

"I am quite proud to be one of the trail blazers in the transition to tertiary education for nurses. I was also active in the Student Nurses Unit of the ANF (now the ANMF) during that time, although not able to become a member due to rules governing union membership; I was not a paid employee as a tertiary student so ineligible.

"I undertook my 'staffing year' at the RAH in 1982, joining the ANF officially on my first day and taking on a 'Key Member' role (now known as Worksite Rep) at the same time ... Brenton undertook his psychiatric nursing certificate at the old Glenside hospital in 1986 and has spent the past 14 years as a Mental Health Nurse Consultant in the FMC Emergency Department.

"I ended up working in the Glenside Casualty Department until its demise in 1996, after which I assisted in setting up the Rural and Remote Consultation and Liaison Team, providing phone-based assistance to mental health consumers and health professionals beyond the metropolitan area for the first time," he says.

"In 2001 I was asked to be a WSR member on the Public Sector EB negotiating team, and subsequently, I applied for a position of Organiser in the ANMF. It was a heady time with fantastic gains made in wages and conditions in the public sector, and subsequent flow-ons to the private sector.

"The most significant campaign of my time was the aged care enterprise bargaining campaign which sought to redress the appalling imbalances in wages and conditions.

It was great to work under the fabulous leadership of Lee Thomas and Rob Bonner, and alongside our current State Secretary, the amazing Elizabeth Dabars, among the many other dedicated officers of our union."

Indeed, ANMF (SA Branch) CEO/Secretary Adj Associate Professor Elizabeth Dabars AM wrote to Brenton on his retirement to express her "heartfelt congratulations and gratitude".

"Thank you for your passion and compassion in the profession. By your actions over the course of your career, you have made an invaluable contribution to mental health nursing and to the union movement," Ms Dabars wrote.

"You have also left an indelible mark on those who you have met. I am privileged to be one of those people."

After his stint with the ANMF team, Brenton returned to clinical nursing, at the FMC, in 2007. He says he loved the "incredible camaraderie" he had with his workmates.

It was also a privilege to be trusted by people (patients) at their lowest ebb, who often disclosed to you their traumas for the first time with any human being, let alone a health professional. Not a day went by where I wasn't humbled by the daily struggle of others, and in the broader ED context, by how life can be changed in an instant. It gives one 'perspective. Brenton says there is an obvious connection between poverty and mental health.

"The easiest and most significant way you could both stimulate the economy and increase people's capacity for life would be to increase welfare payments for people looking for work," he says.

"That money goes straight back into the community because they have to spend it, because they don't have a lot of spare cash, and it also gives them a bit of dignity to be able to afford their accommodation and put food on the table and buy medicines if they need them.

"The mentally ill are often highly represented by unemployment because of their disability and if they're faced with the decision to buy their anti-depressants or put food on the table for their kids, they're obviously going to put food on the table for their kids.

"So then they become unwell and then the whole thing cycles out of control again. We also know for a fact that homelessness increases the chance that someone's mental health will fail or will suffer and that those with a mental illness who become homeless are more likely to end up in hospital.

"Without even looking at the humane side of it, it's the cost to our society and the system to look after people while they're unwell. It's a no-brainer, put the money in at the front end so we don't have to spend more at the back end."

He agrees with his former FMC mental health colleague David Hains that lack of real connection in contemporary society is contributing to our collective mental health demise.

I do think that's an issue. I don't like talking about the 'younger generation' because in my head I'm still only 18, but the reliance on devices and social media to be connected has become a very sad indictment on our society," Brenton says.

"David's exactly right. Whereas kids were encouraged to get on the bikes and ride down the creek and we'd come home with skinned knees and things like that, now everyone's highly conscious about keeping their kids away from danger and unfortunately danger is something we need to learn to navigate in society.

"When I say 'danger', I mean the risk of being disappointed, of falling over and skinning your knee, that kind of stuff. We've got to encourage kids to be resilient and I think that comes from being prepared to take a risk and not being afraid to fail sometimes.

All of this boils down to resilience, and I think we should be in schools teaching kids the skills which develop it. That, and the skills of critical analysis: 'Is news really true or is it fake news being spun for an insincere motive?'.

"Give kids the ability to critically think about the information they're being presented with. Challenge the stereotypes and what have you. I think school's the place (to teach it) because I don't think it happens at home as it probably should.

"It's an indictment when people can tell you who's the favourite to win Big Brother but they can't tell you what the current policy on women is by the Federal Government."

Brenton says one of the most profoundly humbling moments of his nursing career was "the time I had assessed a young woman, well known to the ED, who had struggled for most of her short life with serious mental illness and the effects of significant trauma.

"A colleague felt she might need 'detaining' as she presented as psychotic, but after my review I felt that while she was not well, she wasn't in any imminent risk and likely to be more at risk if we tried to force her into hospital given what that might entail.

"Hence a community option seemed best. We decided to pack her up some sandwiches as she had no food at home and I remembered I had a tub of blueberry yoghurt in the staff fridge which would expire on my days off, so I chose to give it to her instead.

"Her reaction of joy, like a kid on Christmas morning, to be given something of 'luxury', something which to me was going to be thrown out in a few days, underscored to me the all-encompassing poverty our consumers are often forced to endure, through no fault of their own. Sobering."

Click here to read the July 2021 edition of INPractice